“Yes, concerts are experiences—and I’m spending my money on them!”

I explore the impact of prioritizing spending on experiences over material things through my Bruce Springsteen concert experience. With a bit of help from Amit Kumar’s research.

Advertisement

I explore the impact of prioritizing spending on experiences over material things through my Bruce Springsteen concert experience. With a bit of help from Amit Kumar’s research.

In my previous MoneySense column, I wrote about the power of shifting our spending from acquiring things to spending on experiences as it has been shown to create lasting satisfaction in our lives. Now, let me put that to the test. Here is my real-life personal story that highlights the profound impact of spending on experiences instead of material possessions. But before I get to that, think back to your favourite concert. Who was on stage? Where were you? Who was with you? Which song kicked off the night? And what was the unforgettable encore that had everyone buzzing with euphoria?

Allow me to share my story.

Music was a constant presence in my life growing up. During car rides and at home, my parents sang along to classics such as “Fishing in the Dark,” “Standing Outside the Fire,” “Copperhead Road,” “Summer of ’69” and “Bad Moon Rising.” Those songs bring me joy even now.

Music can act like a time machine, transporting you to specific periods or moments in your life, while also allowing you to fully embrace and relish the present, immersing yourself in emotions, sensations and experiences. Music can help us savour life. And, it gives a nostalgic feeling that you’re probably experiencing as you read this. But I digress—let’s focus on why spending our money on experiences can be a catalyst for enduring happiness, especially relative to material purchases.

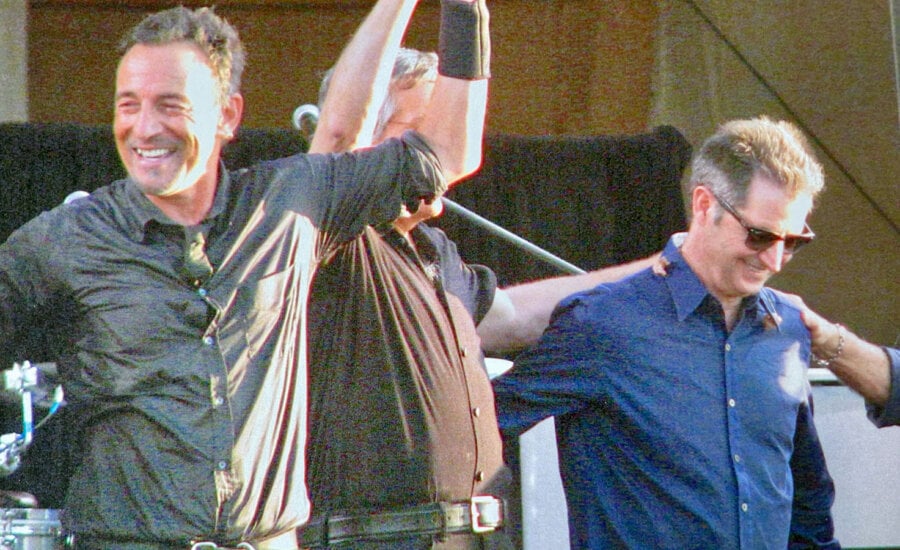

For me, Bruce Springsteen’s resonating voice was a fixture in our home. His music was a symphonic blend of captivating lyrics, energizing guitar riffs and thundering drums. Springsteen and the E Street Band became a part of my family’s lives. My two brothers and I were fortunate enough to witness the band live. However, our parents, who had introduced us to so much music, hadn’t yet.

Then, an opportunity arose. Springsteen was playing at the 2014 New Orleans Jazz Festival. Our parents loved New Orleans, and my brothers and I surprised them with tickets. Despite their initial concerns about costs, the idea of us singing shoulder to shoulder under the New Orleans sun was too irresistible.

We did the math, found affordable accommodations and flights, and immediately booked our tickets. From that point on, we immersed ourselves in Bruce’s music, watching old concerts and attempting to predict the set list, eagerly anticipating the concert. The excitement grew as the months passed, and our countdown to “BRUCE IN NEW ORLEANS” became a daily ritual.

Finally, the day arrived—May 3rd, 2014. We arrived at the festival’s main stage six hours early to secure a prime spot. The anticipation was palpable. The sun was scorching, but our spirits soared. When Bruce took the stage and greeted the crowd, the rush of emotions was overwhelming. The music began, and we sang, swayed and smiled for hours on end. It was a moment of pure, unadulterated happiness.

Though the concert was quickly over (if three hours can be considered quick), the memories remain vivid. Almost a decade later, remembering that night fills me with joy, gratitude and happiness.

So, why do I share this story? Looking back now, I realize how pivotal this experience, and other similar ones, have been for my overall well-being and happiness. The cost of the trip, though significant, pales in comparison to the average yearly expenses associated with owning a vehicle—around $12,000 in Canada, according to Ratehub.ca (Ratehub and MoneySense are both owned by Ratehub Inc.). And most Canadians spend this amount without much consideration or reflection on how it impacts their well-being. I’m not suggesting we stop using vehicles. It’s more about the amounts of money we spend on them. Does owning a $40,000 or $50,000 car give more life satisfaction, say, compared to one worth $15,000 or $25,000 that’s reliable and safe? Author Ramit Sethi writes in his book I Will Teach You to Be Rich (Workman, 2019): “Spend extravagantly on the things you love and cut costs mercilessly on the things you don’t.”

My New Orleans adventure, including travel, tickets and accommodations, totalled approximately $2,000 per person.

When I weigh this cost against the research of Amit Kumar, assistant professor of marketing and psychology at the University of Texas at Austin, which suggests that spending money on experiences rather than on possessions creates more enduring satisfaction, the significance becomes crystal clear. I know it seems counterintuitive, but the research is so conclusive: experiences matter. Of course, we need to take care of our basic needs, but spending discretionary income on experiences increases our well-being more than acquiring material possessions. This makes me pause and reflect on how I wish to spend my discretionary income. While I acknowledge the necessity of buying material possessions, when I reflect on the most cherished moments of my life, they often revolve around experiences.

In essence, seeing Springsteen in New Orleans is an example of how prioritizing experiences over material items is good.

Does this mean we need to all go out and recklessly spend our money on lavish experiences? No. We still must be responsible and diligent with our money. I’m not suggesting a YOLO approach to spending all your money on experiences. Instead, I’m saying it’s an opportunity to reflect on how you are currently spending your money. I’m inviting you to consider the financial trade-offs and to learn how to balance them.

Could you reallocate some of the money spent on material purchases toward experiences as a means to derive more enduring satisfaction? Of course. Money is about decisions.

We spend a lifetime making decisions on how to spend our money. For most of us, we aspire to lead a good life, where, at the end, we can proudly say, “I did it—I lived a good life.” Often we get comfortable spending our money on things we think we should be buying. Perhaps Kumar’s research can help you recognize that spending money on experiences matters. They matter significantly, considering that our future selves are an accumulation of the experiences we have had in our lives. Personally, I apply Kumar’s research and insights to my discretionary income, with the hope that when I reach the end of my life, I can say, “I did it. I lived a good life.”

If you are interested in hearing from Kumar himself, check out episode #150 from The Most Hated F-Word Podcast, where I interview him.

Share this article Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linkedin Share on Reddit Share on Email